In the 16th century, a Brazilian tree with the scientific name “Anacardium occidentale” was introduced to the sandy soil of India (1). The cashew tree was an advantageous addition to the Indian climate. This tree, unlike other fauna, grew exceptionally well in sandy soil, and was successfully used to control erosion (2). Today, the cashew tree holds India together in a much less literal way. India is one of the world’s leading cashew producers and cashew processors. In 2018 alone, they produced more than 860,000 tons of raw cashews (3). Unfortunately, the cashew market is marked with tragedy and exploitation. Caustic oils from cashew shells damage the hands, eyes, and lungs of cashew shellers. A change in cashew processing is sorely needed, and consumers could reduce harmful practices with ethical purchases.

This paper will cover three aspects of the cashew market: a broad summary of global exportation and farming, the damaging working conditions in many processing facilities, and the current and potential effects of US consumption choices.

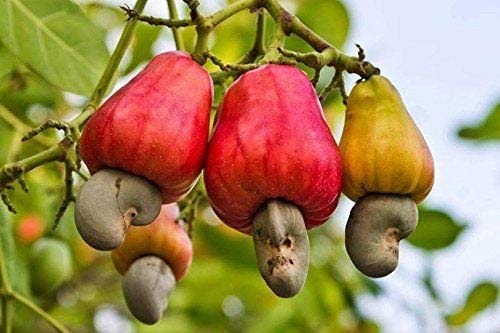

For most of us, the image of a cashew shell is completely foreign. Cashews grow as little fruits in small clusters. The ends of tree branches are attached to the cashew apple, a fleshy portion about three inches long which looks (and tastes) like a cross between a bell pepper and a mango (4). The cashew nut we recognize is called the kernel, and grows below the fruit in a kidney-shaped shell (5). In the American grocery store, cashews are labeled “raw” to mean “not roasted,” but in the global market, raw cashews refer to kernels which haven’t been shelled yet.

Cashew trees require warm temperatures and consistent rain (5). The largest cashew-producing countries are close to the equator, but cashew farms are not heavily centralized. Today, Vietnam produces the most cashews, but comparably large quantities come from West Africa, India, the Philippines, and Brazil (3). In many instances, cashews are grown and processed in two different places. Large portions of West Africa’s crop, for example, is processed in India (6).

In the 1920s, the Indian Nut Company introduced cashews to the global market, specifically advertising the tasty nut to the large population of the United States. By commercializing cashews, India transformed its country into the ultimate cashew king. Processing facilities expanded to accommodate a new scale of production, and kernels were quickly solicited from other countries (7, 8). India dominated the cashew industry for more than 70 years, but in the late 90s and early 2000s, Vietnamese businessmen remodeled the cashew processing system, and revolutionized the cashew market. India was reluctant to apply the same innovations to their own cashew processing systems, because they were afraid they’d lose jobs. Vietnam’s cashew exports overtook India’s exports extremely quickly. Since cashew processing was quicker and cheaper, Vietnam bought African cashews for a higher price and sold their processed cashews for a lower price (9).

The international dynamics in the cashew market suggest that cashew-processing systems are crucial to the market as a whole. This is completely true! Cashews are one of the most complicated crops to process, and must meet rigorous international food safety standards. Cashew shells have two layers. Between them lies an oily resin which is deadly enough to make a kernel completely inedible. Shells have to be broken in a way that prevents the kernels from touching oils in the inner shell. The problem-causing compound is known as urushiol. This is the same compound produced by poison ivy, and blisters skin on contact (8).

A recent guidebook on cashew processing details the three main strategies for accessing the kernel. The cheapest option is known as “drum roasting.” Shelled cashews are fed across a hot, slanted drum, which burns off the urushiol and makes the shells brittle enough to crack. This method is not popular: drum roasted cashews have difficulty meeting safety standards, and some cashews are too scorched to sell. “Oil bath roasting”, another method, draws caustic cashew oil into a surrounding bath. The extracted resin (known as CNSL) has significant market value of its own: it’s used in the production of polymers, paints, and adhesives, among other things (11). The last method, “Steam & Cut,” is the most popular. In this method, raw cashews are kept under high-pressurized steam, and shells are cut open long-ways to retrieve the kernel. Steam & cut cashews are whiter and safer to eat, but this method doesn’t remove the urushiol from the shells. Like the other two methods, human workers have to finish de-shelling cashews with their own hands, but steamed cashews can be risky to work with because they still contain concentrated levels of urushiol (10)

In 2011, Time Magazine published an article which drew attention to the difficult working conditions of cashew processors. This article went for the shock-factor: Many Vietnamese drug-rehabilitation centers were coercing detainees into 10-hour days shelling blister-causing cashews. (Strangely, relapse rates were very high.) Men who didn’t work were beaten and electrocuted. Men who did work burned their hands and coughed on cashew dust (12).

Luckily, prison labor in modern Vietnamese cashew factories is a marginal phenomenon. But serious and wide-spread safety issues affect hundreds of thousands of Indian and Vietnamese cashew shellers (13, 15). In India, most cashew-shellers are paid by weight, so quicker shellers make more money. Many people choose to work without gloves to increase their speed. Others do not have access to gloves at all (15). Vietnamese workers face similar health issues, and work in factories with extremely low safety regulations (13). Cashew processors endure the cruel conditions because they lack quality options.

Cashews are the 4th most popular nut worldwide (16). It is a huge market. America is a major figure in the cashew industry, since American cashew consumption tops every country but India (17.) Several years ago, the International Nut and Dried Fruit Council published statistics demonstrating the global cashew demand had increased by 50% from 2010 to 2017. The modern popularity of veganism has contributed to the increased demand: cashews are commonly used to replace milk and cream in vegan recipes (24).

Is it appropriate to value cashews when production cruelty is widespread? Yes. Poor working conditions should not be ignored or left unaddressed, but cashews are still an extremely valuable resource.

In America, heart disease is the leading cause of death (18). Cashews, among other nuts, can decrease the risk of coronary heart disease by 37%. Nuts help people maintain healthy weights by increasing metabolism and helping people feel full. Cashews are low in cholesterol and saturated fat, and contain about 83 mg of magnesium per ounce. Magnesium improves the body’s reaction to calcium and decreases the risk of kidney stones, osteoporosis, and artery calcification. Cashews contain copper as well, which is important for bone health and for replacing damaged tissues in joints (19). Just as importantly, cashews are delicious. A pinterest-related snack board jokes that “mixed nuts are just cashews with obstacles.”

Choosing to buy ethically-based cashews is a much more effective response than giving up cashews altogether. How? Ethical purchasing choices increase demand for fair and transparent practices. Responding to well-treated workers with money will increase opportunities which are currently available and encourage reform in unethical practices. Cashew processing factories in India and Vietnam are very susceptible to market pressures, and care a lot about responses of American consumers.

Ethical cashews can be bought online very easily. One great brand is “East Bali Cashews” which can be found on Amazon (21, 22). Other options can be found on the equal exchange website. When shopping in a real store, look for reliable certifications such as fair trade.

Sources:

(1) “Cashew Nut Industry and Exports.” India Brand

Equity Foundation. 2019

https://www.ibef.org/exports/cashew-industry-india.aspx

https://www.ibef.org/exports/cashew-industry-india.aspx

(3) “Top 10 Country Production of Cashew nuts, with

shell.” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2018

http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#rankings/countries_by_commodity

http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#rankings/countries_by_commodity

(4) Bruno, Joey. “What does Cashew Fruit Taste

Like?” Thrive Cuisine. Feb 5, 2019

https://thrivecuisine.com/taste-test/what-does-cashew-fruit-taste-like/

https://thrivecuisine.com/taste-test/what-does-cashew-fruit-taste-like/

(5) “Cultivating Cashew Nuts.” Department of

Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries: Republic of South Africa.

https://www.nda.agric.za/docs/Infopaks/cashew.htm

https://www.nda.agric.za/docs/Infopaks/cashew.htm

(6) Schwartz, Elaine. “The Travels of a Cashew.”

Econ Life. Dec 5, 2017

https://econlife.com/2017/12/cashew-globalization/

https://econlife.com/2017/12/cashew-globalization/

(8) Baron, Matthew. “History of the Cashew.” Bulk

Nuts, May 1, 2017

(9) Krishnakumar, P. “Vietnam eats into India’s

Cashew Export Plans.” The Economic Times, Jul 28, 2017

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/vietnam-eats-into-indias-cashew-export-plans/articleshow/59807531.cms?from=mdr

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/vietnam-eats-into-indias-cashew-export-plans/articleshow/59807531.cms?from=mdr

(10)

Weidinger, Reita, et

al. “Guidebook on the Cashew Processing Process.” German Cooperation,

Competitive Cashew Initiative, June 2019.

https://www.comcashew.org/imglib/downloads/2019/Guide%20Book%20on%20Cashew%20Processing%20Process.pdf

https://www.comcashew.org/imglib/downloads/2019/Guide%20Book%20on%20Cashew%20Processing%20Process.pdf

(12)

Marshall, Andrew. “From

Vietnam's Forced-Labor Camps: 'Blood Cashews'” Time Magazine, 2011

http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2092004,00.html

http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,2092004,00.html

(13)

“Cracking the nut:

Understanding labour abuses in Vietnam’s cashew industry.” Ethical Trading

Initiative, Dec 4, 2018

https://www.ethicaltrade.org/blog/cracking-nut-understanding-labour-abuses-vietnams-cashew-industry

https://www.ethicaltrade.org/blog/cracking-nut-understanding-labour-abuses-vietnams-cashew-industry

(14)

“Information about

Cashew Processing in India.” Shelling Machines, 2014.

https://www.shellingmachine.com/application/cashew-processing-India.html

https://www.shellingmachine.com/application/cashew-processing-India.html

(15)

Drewett, Zoe. “Women in

India Pay the Price for Cashew Nut Demand as Vegan Diets Rise.” Metro News,

April 4, 2019

https://metro.co.uk/2019/04/04/women-india-pay-price-cashew-nut-demand-vegan-diets-rise-9110415/

https://metro.co.uk/2019/04/04/women-india-pay-price-cashew-nut-demand-vegan-diets-rise-9110415/

(16)

Kiprop, Victor.

"The Most Popular Nuts in the World." WorldAtlas, Dec. 13, 2018

https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-most-popular-nuts-in-the-world.html

https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-most-popular-nuts-in-the-world.html

(17)

“The West African

Cashew Sector in 2018.” Nitidae, June 2019

https://www.nitidae.org/files/41dc7432/wa_cashew_sector_review_2019_nitidae.pdf

https://www.nitidae.org/files/41dc7432/wa_cashew_sector_review_2019_nitidae.pdf

(18)

“Leading Causes of Death.”

CDC, 2017

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

(19)

Ware, Megan. “Health

Benefits of a Cashew.” Medical News Today, June 18, 2018

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/309369#benefit

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/309369#benefit

(20)

Souza, R. et al. “Nuts

and Human Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review.” National Center for

Biotechnology Information, Dec 2, 2017.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5748761/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5748761/

(21)

East Bali Cashews,

variety pack. Amazon.com

https://www.amazon.com/East-Bali-Cashews-Variety-Cashew/dp/B07CZX2QT1/ref=sr_1_1_sspa?crid=2L2F9GM91IOTZ&keywords=east+bali+cashews&qid=1583416816&sprefix=east+bali%2Caps%2C155&sr=8-1-spons&psc=1&spLa=ZW5jcnlwdGVkUXVhbGlmaWVyPUEyUzhYR1JGMzhINlZCJmVuY3J5cHRlZElkPUEwNjc4MjY3M1ExWDM4R0E4VkNYUCZlbmNyeXB0ZWRBZElkPUEwMDk4Njk0MzVLS1dWRTBZT0dENiZ3aWRnZXROYW1lPXNwX2F0ZiZhY3Rpb249Y2xpY2tSZWRpcmVjdCZkb05vdExvZ0NsaWNrPXRydWU=

https://www.amazon.com/East-Bali-Cashews-Variety-Cashew/dp/B07CZX2QT1/ref=sr_1_1_sspa?crid=2L2F9GM91IOTZ&keywords=east+bali+cashews&qid=1583416816&sprefix=east+bali%2Caps%2C155&sr=8-1-spons&psc=1&spLa=ZW5jcnlwdGVkUXVhbGlmaWVyPUEyUzhYR1JGMzhINlZCJmVuY3J5cHRlZElkPUEwNjc4MjY3M1ExWDM4R0E4VkNYUCZlbmNyeXB0ZWRBZElkPUEwMDk4Njk0MzVLS1dWRTBZT0dENiZ3aWRnZXROYW1lPXNwX2F0ZiZhY3Rpb249Y2xpY2tSZWRpcmVjdCZkb05vdExvZ0NsaWNrPXRydWU=

(22)

Beaver, Hannah. “15

Ethically Sourced Snacks You can Feel Good About Eating,” Spoon University,

2018.

https://spoonuniversity.com/lifestyle/15-ethically-sourced-snacks-you-can-feel-good-about-eating

https://spoonuniversity.com/lifestyle/15-ethically-sourced-snacks-you-can-feel-good-about-eating

(23)

“Organic Natural

Cashews.” Equal exchange

https://shop.equalexchange.coop/collections/fruits-nuts/products/organic-natural-cashews-8oz

https://shop.equalexchange.coop/collections/fruits-nuts/products/organic-natural-cashews-8oz

(24)Parsons, Rhea. “10 Vegan Food Hacks with Cashews.”

One Green Planet, 2018.

https://www.onegreenplanet.org/vegan-food/vegan-food-hacks-with-cashews/

https://www.onegreenplanet.org/vegan-food/vegan-food-hacks-with-cashews/